Ah the good old days!

When Edinburgh was graced by beautiful horses, a comprehensive tramway system, decent roads, happy visitors, and a popular Council firmly in control of private-sector subcontractors, operating across all departments with efficiency and purpose.

Two letters which appeared in the Scotsman on 18 and 22 December 1869 cast an interesting light on distinctive features of nineteenth-century Edinburgh street life; some of which are thankfully lost, others of which sound rather familiar.

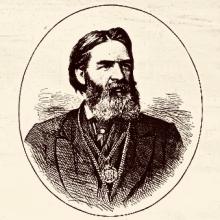

For those who like detail, the first correspondent, Thomas Knox, lived from 1818–1879 and is buried in the Grange Cemetery. At the time of this letter, he resided at 2 Dick Place, and was a partner in Knox, Samuel, & Dickson, ‘fringe and gimp manufacturers, hosiers, glovers, and smallware merchants, jewellers, and perfumers’ at 13, 15, 17 Hanover Street and 42 Rose Street. They had a factory on Mound Place. Knox was Master of the Edinburgh Merchant Company in 1872, when the portrait top-right appeared in the Graphic.

The long paragraphs below are as they appeared in the original, and were considered perfectly normal by serious-minded Victorians with good eyes. The subheadings below are ours, inserted for the benefit of 21st-century readers using mobiles/tablets, who might otherwise begin to feel giddy and disorientated.

SIR,—When things are at their worst they generally begin to mend. This consolatory proverb will, I think, not be exceptional at this time. Ameliorations of the coarser outward forms of oppression and cruelty to the tramway horses are mercifully becoming visible at last—what may be called the grey dawn or twilight of a new day, alike for the keen feelings of horses and citizens. None of all those who have taken the public stand to plead and protest on behalf of the horses—the noble companions of man—so oppressed and abused from day to day and hour to hour in our public thoroughfares, will ever regret it. On the contrary, they must feel that to have seen poor dumb creatures, by nature so loyal and so subservient to us in every form of work or pleasure, and have cried aloud against their oppressors, would have been to deliberately forfeit both citizenship and manhood. To be dumb creatures from necessity is a sad thing, but to be so from choice is an infinitely sadder thing.

But while, by the energy of Mr Linton, our Superintendent of Police, also Mr Brown, the Secretary of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, such a needful degree of relief has already been wrought, let us not conclude that the evil is cured and ended. The coarse drivers who tug at the horses’ mouths like masons’ labourers tugging at an old gable, and the scorpion-postilions of Arab boys, with remnants of shirts through half-rotten “breeks,” not so likely washed last week as last year, hanging ornamentally down the thin wicker-work sides of their victims of trace-horses—I say the worst phase of that disgusting sort of thing is only a secondary symptom of the cruelty and oppression, and we must go deeper to seek for permanent amelioration, if not absolute cure. If we don’t, our public streets will be converted steadily into an amphitheatre for a rival pastime to the bull-baiting and like cruelties of the brutal, bloody-minded Spaniards. Literally the lower classes in all classes will get the base gratification of seeing horse-beating gratis whenever they choose to step out to our thoroughfares, if the right-minded citizens don’t with one indignant voice continue to denounce and protest.

Stupidest invention ever launched

The root of the oppression and cruelties is first in the construction and weight of the tramway cars in relation to such gradients—steep hills, small Arthur Seats, actually. The stupidest invention for such streets and circumstances ever launched is the tramway car. Licensed to take five tonnes weight or so of wood and iron materials, and men, women, and children, up young Arthur Seats, called North Bridge Street and Leith Street, with a set of horses often so spiritualised and attenuated that a close observer might see through them and the number of the policeman standing at Cranston & Elliot’s door, or the price of Mr Roy’s rich and rare articles of “juvenile dresses” with the naked eye. Just think of it. Only the miraculous agency of whip-cord on ancient well-bred horses’ legs could make the animals spasmodically struggle through with it, to the infinite horror and disgust of inside and outside passengers and the public. One would like to hear the autobiographies of some of these horses from their own bleeding mouths and lips—their rise and progress in petted studs for hunters and racers before their decline and final fall into the street shambles of the Tramway-car Company. As a correspondent which I quoted in my last letter said, such cruelties may well bring down a judgment upon the city. The attention of Messrs Moody and Sanky, the zealous American revivalists, is earnestly directed to this threatening subject. We understand that their public prayers are specially put up for “females falling into drink.” As a life-long abstainer from all intoxicants, I can say that is well; but surely while that is done, this for “a great city falling into disgrace,” need not be left undone—public prayers that the Tramway Company may reconsider the size of the Juggernaut Cars, the steepness of the North Bridge Street and Leith Street gradients, the open oppressions and cruelties to their horses, the great disgrace of the city, and great danger to the citizens. Also the Town Council for not interposing its strong arm to arrest the municipal grievance. How many venerable citizens would they like to see sliced alive by accident in the public streets before they “tak’ a thocht and mend” such a shocking state of things daily?

Dilemmas for Tramway Company and Town Council

The Tramway Company cannot escape from one or other of the horns of this dilemma—either they have proper machines or improper horses, proper horses or improper machines. In consideration of the gradients and the great tonnage, any man can see that they both are improper, and deservedly under the heavy ban of outraged public feelings and opinion. Nor can the Town Council escape from this other dilemma—either they have the power, or they should have it, to make every such minor public company subserve the safety of the entire community. Conductors of tramways independent of drivers, and drivers independent of conductors, and trace-horse boys under the authority of neither, is a state of things which for culpable laxness of arrangement was perhaps never equalled. Whether the driver was ever properly accustomed to drive or the boy to guide a horse is all according to the doctrine of chance—accident—as far as any official guarantee is given or known. And when, it may be, sheer incompetency runs down a citizen, old or young, that too is classified under “accident”. Can a Town Council of Edinburgh rest satisfied with such corporate criminal laxness, such a preponderance of “accident” pervading departments, where precision and authority should be felt pressing all round as an atmosphere.

Municipal mystery

That a Road Trust or Paving Board should also be able to afflict the traffic of Edinburgh of all kinds with such dangerous pavements on such steep gradients without challenge from the Town Council in the interest of the whole community, is another municipal mystery which no fellow can find out. A pavement so hard and so sloped that horses would require to be clever as Blondin to steady themselves and do duty without scaith to legs or necks. Along small mountain-ridges of stones hard as flint or “glass bottles” in the centre of the public streets, is the problem which man and beast have to solve daily in our city, on penalty of broken necks, or ribs, or legs. The panic of fear which overtakes horses heavily loaded with lorries, who get no safe and firm foothold, often bathes them in sweat as if they had swam through the Frith of Forth. To see the inevitable increase of traffic, is to realise a time near at hand when Edinburgh visitors for pleasure will become small by degree and lamentably less. For what pleasure will be found in walking public streets and thoroughfares to hear the thunder-clatter on the pavements of agonised horses that cannot get foothold for their work? Or finally, to see them wearied and cast down, by their hopeless struggles upon adamantine pavement? What pleasure to see tramway horses staggering, stupid and choked-looking with their oppressive cars, and hear the lashing and swearing of drivers and boys, as if this was not far-famed Edinburgh but “the other place?” The Baroness Burdett Coutts has laid us all under a deep debt of obligation by helping us to amend such evils, but other illustrious strangers may feel rather constrained to avoid than amend such outrageous and harrowing exhibitions.—I am, &c.,

THOMAS KNOX.

*****

5 South Berkeley Street, Portman Square, London, W. 19th December 1873.

SIR,—I have read in your journal of the 18th inst. the letter about the tramways signed Thomas Knox. There is not a statement in that letter, with regard to the tramway horses, that is exaggerated. Having been in Edinburgh for two days this week, I witnessed scenes of cruelty to the horses under the tramway cars which are a positive disgrace to a city like Edinburgh. The horses employed to draw these cars are entirely too light, and are most miserable in condition. In fact, I don’t think they could be otherwise under such hard work. They are wholly unfit to do the work at which they are employed. Even four horses drawing a tramway car up Leith Walk it is painful in the extreme to witness, and my only wonder is why the provisions of the Act of Parliament which provide penalties for ill-treating, or abusing, overloading, or over-driving, are not applied. Surely to force horses to do what they are physically almost unable to do, is ill-treatment and abuse, and this I witnessed myself on several occasions during my short visit to Edinburgh.

Until steam power is applied to tramway cars, I think the Legislature ought to hesitate about granting a concession for tramways in such a city as Edinburgh, where there are such steep inclines.—I am, &c.

THOMAS F. BRADY